Today’s dispatch is about the roots of Greenwriting (Bored Wolves, May), a poetry and artist’s book by Katy Bentall for which we have just launched a Kickstarter campaign via www.greenwriting.ink.

I’ll quickly mention that in addition to the book itself, there are two printed-matter rewards available through the campaign in limited amounts: a linocut print of one of Katy’s Tomato Lady characters (24 available out of an edition of 25; I stole the 25th) and her handmade Tomato Ladies zine (just 5 available).

Katy is a prolific maker of brilliantly inventive zines but in very small handmade editions, and so this is a unique opportunity to snag one. This particular zine is a somewhat Gothic tale splattered with tomato pulp (not actually, but Katy uses a lot of red).

Okay, on to the tempeh of this post!

×

There is a particular pilgrimage point connected to the eighteen-month process of developing Greenwriting, Katy Bentall’s collection of drawings, paintings, and a haibun weave of poems and prose dispatches from her patch of the Polish countryside.

The Old Pear Tree Over There

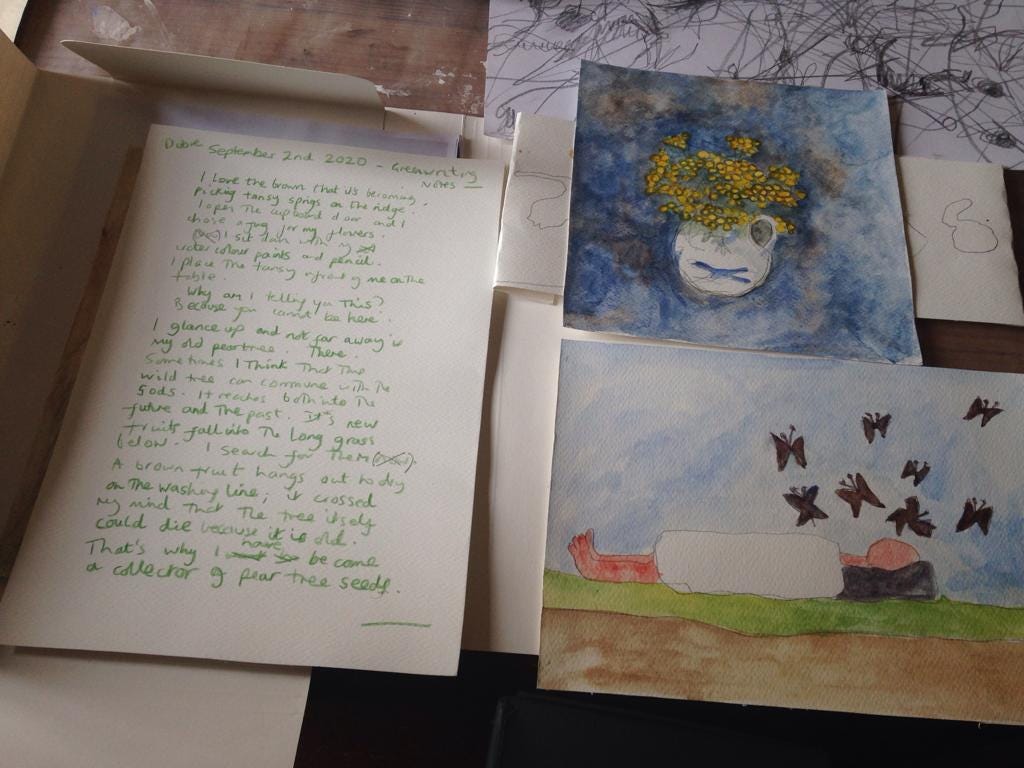

The seed for Greenwriting is “Greenwriting Notes,” a letter Katy composed in green pencil to the missing audience of a pandemic performance she enacted, in sight of the old pear tree in the meadow behind her house, in the summer of 2020. Back then, I described the scene as follows:

“Mapping her immediate world from the table on the balcony where she sits with her notebook, three pears, and a jugful of wildflowers, Katy writes a letter to the unseen viewer of this organic performance. Her pencil is green, her words like grass cuttings all around.”

×

I glance up

wrote Katy, pausing mid-performance,

and not far away is my old pear tree. There. Sometimes I think that this wild tree can commune with the gods. It reaches both into the future and the past. Its new fruits fall into the long grass below. I search for them. A brown fruit hangs out to dry on the washing line. It crossed my mind that the tree itself could die because it is old. That’s why I have become a collector of pear tree seeds.

×

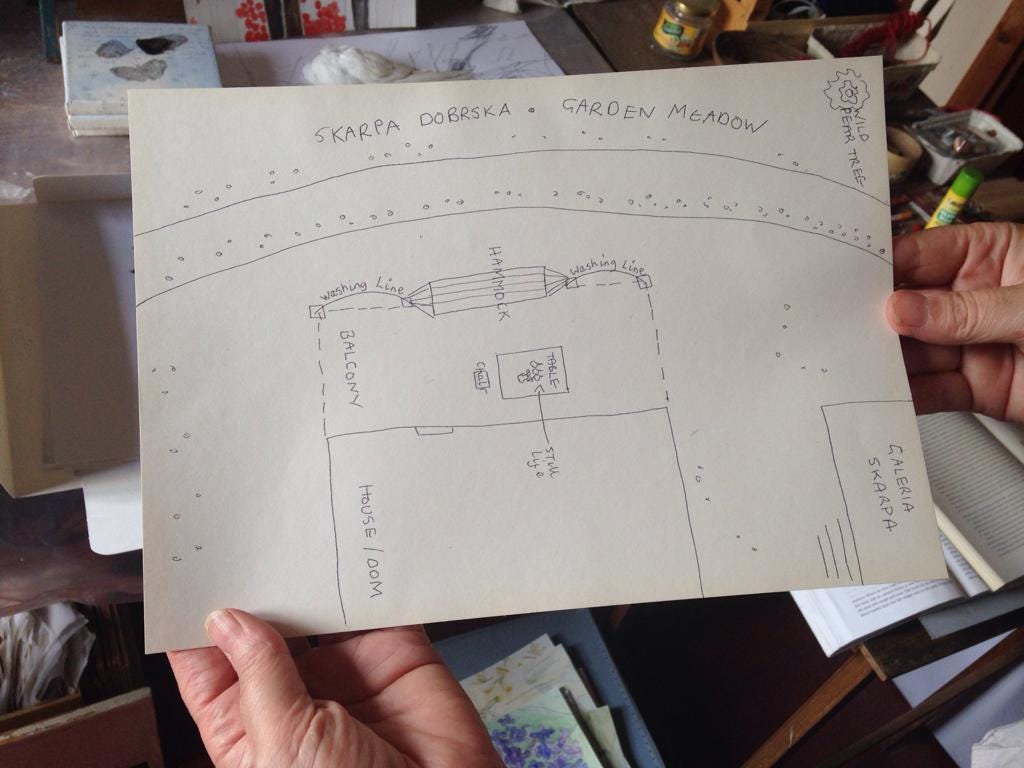

It’s a longer story but despite living only four hours apart for nearly a decade—Katy in her “airy wooden house nestled against the Skarpa, the upland of the Vistula (Wisła) River, famous for its loess valleys, fields of wheat and hops, and orchards of apple and pear,”1 and we wolves in our highland cabin in the Beskid range—it was only through this performative letter, which I was given to edit though I touched not a syllable, that Katy and I began corresponding that first pandemic summer.

At some point, one or both of us wrote:

“Let’s grow a book around this letter!”

“And,” replied both or the other, “call it Greenwriting!”

And here’s where I will retroactively object to a phrasing of mine from above: “Her pencil is green, her words like grass cuttings all around.” Wrong. Because Katy is not a grass cutter. She is a grass whisperer. Not quite. She is a grass listener. From the balcony at the back of her house, she is the conductor of an orchestra of insects. But instead of dictating with her baton she whittles the baton into a pencil, which she uses to make note of the chittering crescendo around her:

I write this as I sit in the / long prickly grasses listening / to the insects hum around me. / If I had cut the grass they would / not be humming / the air would be silent / and I’d be alone.

×

Greenwriting is finished. The letter describing the pear performance, transcribed and typeset, is in the book. “On Greenwriting.” It would have made sense to pride-of-place this original text on the first page, but that’s not where it is.

It is instead buried on page 168, between poems, plenty of prose, and nearly one hundred of Katy’s pencil drawings and watercolors.

What a riot of lushness it inspired!

×

From Louise Steinman’s scrumptiously substantive afterword to the book, “Greenwriting on the Skarpa.”