“It takes an hour and a half to reach Flushing from Sunset Park on the subway. I seem to recall that it used to be only an hour’s ride. If time is not a constant unit of measure, then what is? Only the evidence of time, as in my father’s hands?

“Here is what I picture: when the time comes, I will showcase all that I have of him—my photos of him, the videos, his art, his supplies, his magnifying glass, his dictionaries. I feel like I am catching up to a particular impetus, that of re-creating an archive.”

—Wah-Ming Chang, November 2019

×

In today’s recording, writer, zinemaker, publishing veteran, and initiator of literary communities Wah-Ming Chang reads from her handmade zine Hand, Held: An Autobiography (2023), which she created within the context of developing her forthcoming Bored Wolves literary artist’s book, also entitled Hand, Held, a collaboration with her father, the artist Shih-Ming Chang (to be designed by Sevinç Çalhanoğlu).

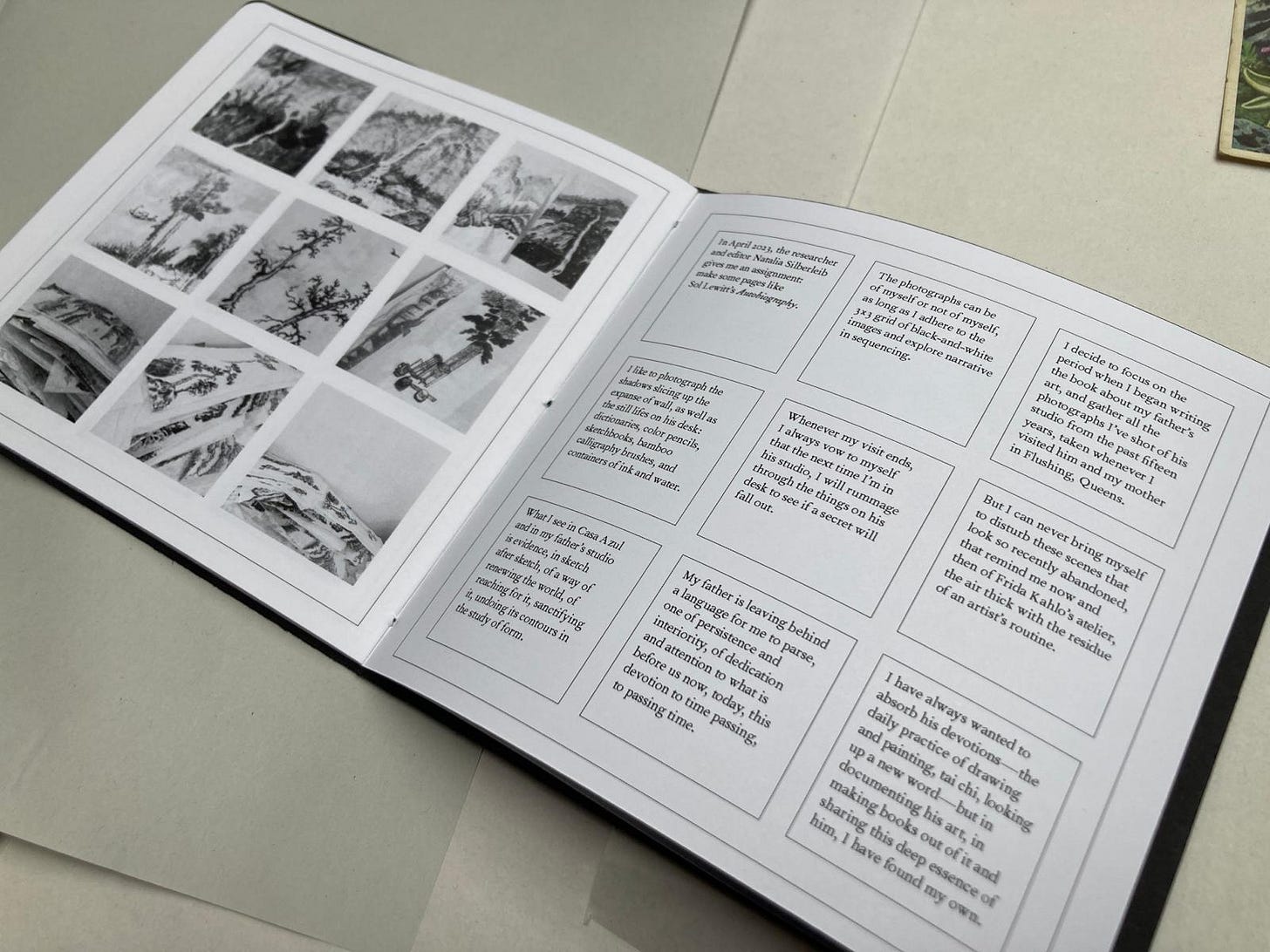

So in the process of developing Hand, Held, Wah-Ming laid out and wrote a proto–Hand, Held in the form of eleven 3×3 grids, the format inspired by Sol LeWitt’s Autobiography (1980), with each grid composed of postage-stamp-sized squares, and the squares framing photographic peeks into her father’s richly inhabited studio-office in Flushing, Queens—the inner sanctum of the whole shebang.

There is also the text Wah-Ming recorded herself reading, itself gridded, which traces the evolution of her process and the project’s metamorphosis into a hybrid monograph-memoir combining decades’ worth of her father’s drawings, paintings, and calligraphy with Wah-Ming’s words and photographs about the art, the studio, her dad, his practice, his daughter, her practice, and how the two communicate using Chinese, English, and Gesture. There are multiple elements and they are all interlocked like knuckly fingers, which is why I am using quite a few hyphens and two lengths of dash.

The resultant zine is, in fact, an entirely self-contained publication (no proto), which I cherish and always have by my elbow because it’s basically a can of WD-40 for the brain. It also now guides the next stage of development, our collaboration with Wah-Ming and Sevinç on the final Bored Wolves edition, because there is no point in reinventing the wheel, which, it turns out, covers ample ground as a square.

×

TL;DR

A dad. A daughter. Two languages that helix into a shared third, a dad–daughter dialect. An artist. A writer. Queens. Brooklyn. Morning. A palindromic route—sidewalk, subway, sidewalk. A room in Queens filled with art supplies and artwork. And paper, very sheaved. And dictionaries, which contain the words in two languages. Reverse route—sidewalk, subway, sidewalk. Evening. A room in Brooklyn where the room in Queens, a glowing memory, is re-created on paper, reflected upon, preserved, and paid homage to. The third language is also preserved. Visits are overlaid. Everything thickens. Fragility is stiffened by such fibrous thickening.

×

“Dad, why don’t I just write about you?”

He smiled shyly.

“Who, me?”